Don't You Worry They'll Have Gaps?

If children don't go to school, how will they ever find new things to learn?

How do children find new things to learn? I'm sometimes asked if I don't worry that self-directed children will miss out on important learning. Here's why my worry is more for children who are at school.

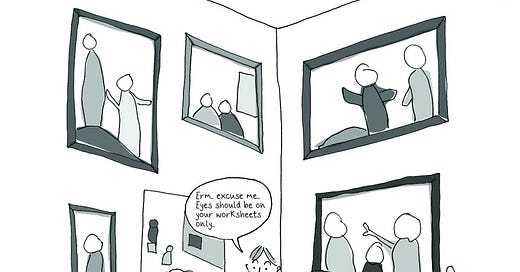

Illustration by Eliza Fricker .Twitter: @_MissingTheMark

School-based education requires children to ignore their interests, in favour of an adult agenda. They are told that the things that fascinate them are less important than the things adults have chosen for them. This happens throughout their day.

In order to keep them 'on-topic', schools limit their access to learning. Talking is restricted, they can't look things up, they can't quickly google a definition (perhaps of the fundamental theorem of algebra,as my son and I did yesterday following the Redactle puzzle).

Schools do this in the deeply held belief that what they want children to learn is more important than what a child finds interesting. Space for children to follow their interests gets smaller and smaller as they grow older.

With the result that by the time they are teenagers, the question 'Will it be on the test?' is more likely than 'Why does that happen?' or 'Can I find out more about that?'. Young people are told from early on that their interests don't matter, and they learn it well.

Even when school children are taken to museums or art galleries, their attention is often directed away from what interests them in the stimulation and beauty around them. Focus is on fitting in the adult agenda, filling in the worksheet and showing their learning.

I used to take my children on trips to the National History Museum during the school day and we would see groups of schooled children, clutching their worksheets. The wonders of the museum were reduced to finding the right answer in the right display cabinet.

My children would move quickly from exhibit to exhibit and sometimes I would worry - should I have brought a worksheet? Should I be making them focus and checking their learning? Should we be doing projects when we got home, related to what we had seen?

Later, I would see that the sparks of interest from that visit kept emerging in unexpected ways. They would play about hatching eggs, or construct a solar system with clay. They would ask questions about important issues like whether baby spiders know who their mother is.

I'd see that the learning from that visit was unexpected and unpredictable, but rich & based on their interests. I'd see that new interests were being added, sometimes fleeting, sometimes lasting. I'd see that any worksheet I wrote would be a distraction from this process.

We make so little time at school for children to practice the skill of following their interest. We dissuade them from seeing something fascinating and running with it. We tell them time and time again that we know best.

Many of us can't imagine another way. We see children's interests as trivial and inconsequential, and adult agendas as important and worthy. We think there would be chaos and lack of 'follow-through' if children could choose what they learnt.

Certainly when they are younger, self-directed children don't 'follow-through' in the way that schooled children are obliged to.They are process focused rather than outcome. This changes as they grow up and start to set goals for themselves.

Research by Barbara Rogoff with Guatemalan children who didn't go to school found that they learnt more than schooled American children from observing the world. The schooled children waited to be told. The Guatemalans were in a state of 'alert awareness'. They didn't expect instruction. They watched other people and events, and they learnt that way.

Most parents have seen this in our young children. They explore the world with gusto, finding topics of interest everywhere. Adults introduce new things and ideas into their lives, but the children pick up some and ignore others. They are free to do so.

This process is then stopped as their primary mode of learning when they go to school. Now it's about remembering what adults tell them. We see the interests of childhood as being trivial and so pulling children away from them to do phonics or maths is accepted as the norm.

But what if that process has side effects? What if following your interests is a really important skill to develop, one which often starts with diggers and dinosaurs, goes through Pokemon and Minecraft and then onto languages, coding, maths and all the other things we can learn?

That's what I worry about, when I see children in art galleries with worksheets. I worry they miss out on the joy of sparking interest and following the trail. I worry that pulling them away has consequences for the future. I worry that they aren’t allowed to see something and suddenly be so curious that they just have to know more. I worry they are learning that what interests them doesn't matter.

So do I worry about self-directed children not finding new things to learn? No. The problem is more how to keep up with them as they find new and exciting things around every corner. The world is full of things to learn when you're interested. Nurture the interest, learning will follow.

This is so well written! I’m going to remember that it takes practice to learn the skill of following our own interests. In a chapter from “Trust Kids” the writer says, “I think it takes courage to stay connected to your child self, and not fall into the norms of society.”