A lot is justified in the name of exam results. It’s okay to control every moment of a child’s day, if the school can show they get excellent exam results. It’s okay to have behaviour policies which put many children in isolation, if the school gets excellent exam results. It’s okay for parents to be complaining, and children to be protesting, if the school can show improving exam results.

Our education system has decided that only one outcome really matters in the lives of our young people. Excellent exam results. When they talk of evidence based education, they mean, what the research shows gets better exam results.

There’s a problem with this, because it’s not possible for everyone to get excellent exam results. Excellence is defined in contrast to everyone else. ‘Good results’ really means ‘better than the others’. An ‘excellent school’ means one that does better than the others, usually measured by exam results. If everyone does very well, it just becomes the norm. They’d have to shift the goal posts.

Half of our young people will always get below average exam results. Not because they don’t try hard, but because an average means ‘the middle’ (and yes I know it doesn’t literally mean that and that there are different ways to calculate an average). There is no way for everyone to get excellent results. Not when compared to everyone else.

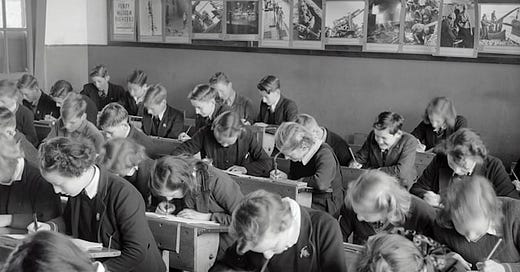

The quest for ever better exam results has a cost. Because it seems fairly clear to me that an effective way to get better exam results from more teenagers is to focus myopically on the test. To drill them in what they will need to do, and only that. To make them self quiz themselves for homework, and to do not just a mock exam, but a mock-mock too. To make school hours longer and to stop off-topic discussions. To punish them if they step out of line and to tell them that their lives will be over if they don’t do well. To coach them in how to take exams, so they become experts in that. To terrify them about the consequences if they don’t spend hours each night on their homework.

All this ‘works’. Some of them will get better exam results than they would have done otherwise.

But there’s a cost. There’s a cost for those who fall by the wayside and stop being able to attend school. There’s a cost for those who get through their exams and then breakdown and can’t go on. There’s a cost for those who submit to all the rules and then still don’t do well, and who spend their lives feeling like failures. There’s a cost to those who develop anxiety, eating disorders and depression. There’s a cost to those who burnout before they are sixteen.

The question we need to reckon with is this. If focusing on excellent exam results inevitably has a cost to the wellbeing of young people, is that cost one we are willing to bear? Are we prepared to write off some young people as collateral damage, whilst lauding those who get the top grades?

Instead what happens is that there is collective denial of the costs. Governments pretend that schools can focus on high stakes test results AND wellbeing, and that there isn’t a trade off there. Schools claim that children are happy to have every moment of their lives controlled, because it makes for a quiet classroom, and that those who say otherwise are the troublemakers.

What if we accepted that an education which prioritises exam results come at a cost, and asked whether this is one we are willing for our young people to pay? What then?

Your article resonates deeply with me because my son is one of the children who paid the price for a school culture that prioritises excellent exam results above all else.

At his previous school, the relentless pursuit of academic accolades under the headmaster’s leadership came at an enormous cost to his wellbeing. The school’s rigid policies and unyielding focus on performance created an environment where children like my son - who needed support, understanding, and encouragement - were instead left to struggle, isolated and marginalised.

My developed severe PTSD as a result of the bullying, neglect, and systemic failures he endured. His once vibrant spirit was crushed by a school that only valued him for his academic potential and disregarded his emotional and mental health. The headmaster’s drive to boast about his school’s "excellence" led to policies that harmed many children, prioritising results over their humanity.

My son’s experience is a stark reminder that the cost of these policies is not hypothetical - it’s real. For every student celebrated for their grades, there are others suffering quietly, their mental health shattered in the process. The headmaster should be held accountable for the harm inflicted on children under his care, all for the sake of bolstering his school’s reputation.

The wellbeing of our young people should never be collateral damage in the pursuit of excellence. It’s time to rethink what we value in education and ensure that no child is left behind or broken in the name of test scores.

This piece needs to be read alongside Peter Gray's #61 BLOG "VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF EDUCATION" - also published today