Tying them Down

The language of 'high expectations' hides the reality of how little we trust our teenagers.

Whenever I talk about high control strategies at school, I’m told that they are necessary because teenagers can’t be trusted. They aren’t going to the toilet to pee, they’re going to vape. If they could talk to each other in the corridors they would be shoving. If they didn’t have hours of homework they’d waste their evenings and fritter away their weekends. Even praying is an act of insubordination rather than worship, when done by a teenager. Let them pray, and the next thing will be anarchy.

Of course, goes the logic, this means that their every move needs to be controlled. There’s no other option.

This sets extremely low expectations for young people. It says, we trust you so little that we won’t allow you to make any decisions at all. It tells them, ‘if we did allow you to make decisions, everything would go wrong. You’d do it badly’.

The result would be chaos, in fact.

How does this fit with creating a culture of ‘high expectations’, often talked about in schools? How can we have high expectations of teenagers whilst showing them that they aren’t trusted to walk down a corridor and chat? What exactly do those ‘high expectations’ mean? It seems like they mean, we expect you to do what you are told no matter what. We expect compliance with no questions asked. No excuses. If you don’t agree, we’ll put you in detention.

This structure reflects very lowest of low expectations. It says, we trust you so little that we will control everything you do, with escalating sanctions for non-compliance. We think that you need to be controlled with fear. We have no faith at all that you are motivated to do the right thing or that what you think matters.

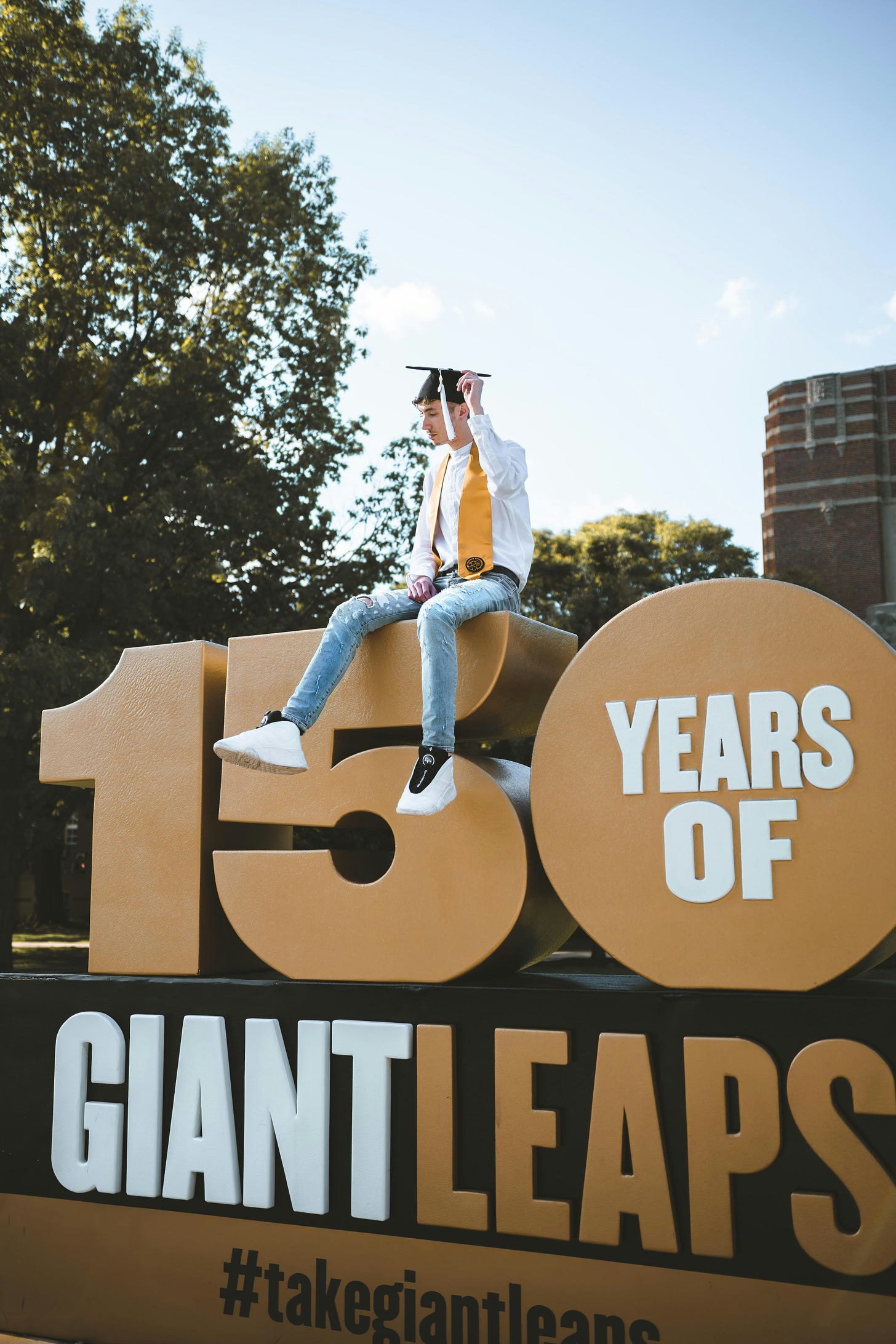

This can’t help but have an impact on young people. For high expectations aren’t just about what we say. They are in the air that we breathe, the atmosphere which young people live in. If the culture and systems of a school communicate that ‘teenagers aren’t trustworthy’ then the real expectations are rock bottom. No matter how many signs are on the wall exhorting them to aim for the stars or ‘make giant leaps’.

There’s no space for giant leaps when you think that ‘high expectations’ means others controlling every choice that you make. When we teach our teenagers that, we tether them down. We hobble them. Compliance makes them easier to manage now, but at a cost for their future.

For to leap high, you need people who have faith in you, even when you make mistakes. You need people who will catch you when you fall, and will let you try again. You need to see the confidence of others in you, so you can find your own. And you need the space to make your own choices, and through doing so, learn how to manage yourself in the world.

Without that in place, ‘high expectations’ aren’t high at all.

Very very true and interestingly the restrictions on children for compliance increase as they get older when you’d think that we’d recognise that they are developing some control as they grow up. Look at any early years classroom and the 4-5 year olds have autonomy to choose who to play with, what to play with and for how long for the majority of their day. Hit Y1 and this instantly decreases. Fast forward to Y6 and children have to ask to leave their seat to sharpen a pencil. Move into secondary school and its detention for having the wrong shoes. Where did that autonomy go? We bred it out of them by our requirement for ‘behaviour management’ in classrooms and our lack of trust in their ability. If we want our young people to be high flyers, they need to experience and be ok with making mistakes along the way rather than assuming everything has only one correct answer. We need to teach them to be curious, explore and get things wrong, then ask why and help each other. Sadly far too few schools offer that process to our teenagers who are at a stage where they need it as much as the children in early years do.

I try and teach my adolescent students how to be independently accountable and integrity. It requires me to let go of trying to control every move they make, allowing them to mess up sometimes, and be held accountable.

My biggest struggle is how students can re-earn my trust after repeatedly breaking it. How can I trust students when I’ve been burned so many times? How do you handle this with teenagers?